Single Parenting by James Windell

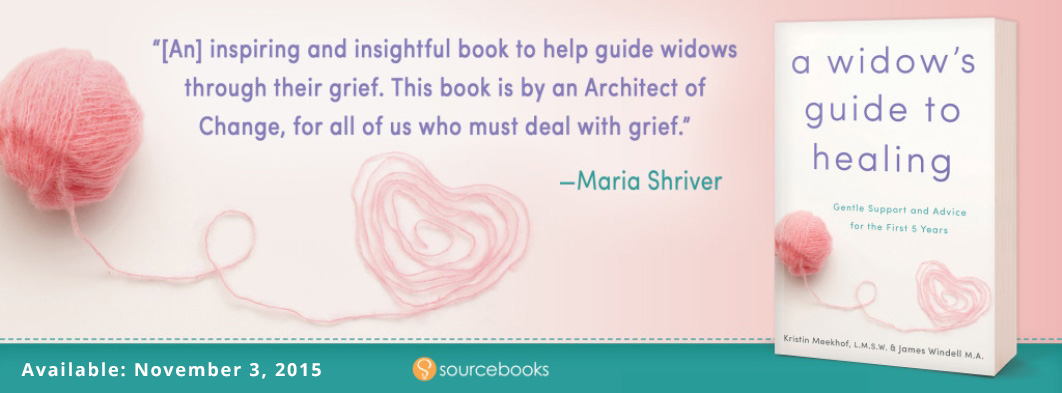

I’m currently writing a book for widows to help them better cope with the changes that come about after a woman loses her husband. My co-author is a woman who lost her husband to a rare form of adrenal cancer. Many of the dozens of women we have interviewed also had husbands who died of some form of cancer.

To many of us adults it seems that cancer is an epidemic which strikes with amazing frequency. The American Cancer Society indicates that half of all men and one-third of all women in this country will develop cancer during their lifetimes. And according to the Centers for Disease Control, cancer is the second leading cause of death among adults in the U.S. – just behind heart attacks.

This means that every family will be touched by an illness or death of someone due to cancer. As we have discovered in interviewing widows, it also means that children are exposed to the “C word,” and if adults are frightened by cancer imagine what it must be like for children when they hear that a parent or family member has cancer.

How do you explain to a child that a loved one has cancer?

As with so many other situations in life to which kids are exposed, the more information they have the better they will cope. Therefore, as much as you would like to shield your child from the pain and suffering of a parent or another family member, trying to ignore or avoid using the C word is not likely to really help them in the long run. If you avoid talking to a child about the cause of the person’s illness, you can be sure that they will rely on their imagination and fantasy to try to understand cancer. That could well be worse for them because of the possibilities of false concepts or ideas.

For instance, I was talking to a recent widow who said she finally told her young children that their father had cancer, but while it was helpful to know why he was in the hospital and what kind of treatment he was receiving they were convinced he was recovering and would be home soon. They talked frequently about their daddy coming home and being able to do things with them just like he did before he got sick. When she was assured by the doctors that her husband’s cancer was untreatable and would be fatal, it broke her heart to have to tell them the sad news.

“I didn’t want to destroy their faith and optimism,” this mother said, “but I couldn’t let them go on believing their daddy would recover and be home again.”

To prevent children having misconceptions, the best approach is to tell them about the illness and do this in a simple, straightforward way.

For a younger child, it can be as simple as saying, “You father is sick and has to go to the hospital. He will have some strong medicine, but we are pretty sure he will be able to come home and you can see him then.”

For an older child, the explanation can be more detailed: “Your father is sick with an illness called cancer. That means that he will have to have an operation to get rid of the cancer. After that he will have treatment with very strong medicine, but we think he will be just fine and will be coming home after that.”

As children get older, they can be provided with more medical and scientific information about the exact nature of the cancer. Younger children don’t need such detailed information; more often they are in much greater need of reassurance.

One way to provide such reassurance is to let them know they did nothing to cause the illness, particularly if the person with cancer is a parent or sibling. You can say, “No one knows what caused your mother to have this kind of cancer, but we do know that people can’t make it happen. Also, people don’t do anything bad for it to happen to them.”

There will be many questions that a child will have when a family member develops cancer. It is always better to answer questions as honestly and as openly as possible. It has been found in research studies with families that when there is open communication children experience much less distress.